By guest blogger, Tracy Kedar

A few weeks ago my friend’s elderly father was hospitalized. At the time he was confused, agitated and had worrisome physical symptoms. A doctor told my friend that she should place her father in a hospice, that his death was imminent. “What?” she responded, “He was driving just last week!” “Well,” said the doctor abruptly, “he isn’t now.”

Today he is back home, back on his feet, and more active than he has been in months following the correct treatment of his symptoms by a different doctor. “What that doctor did was rob me of my hope for my father. I was crushed by his verdict and he turned out to be completely wrong,” she told me.

How can we fight when we are told something is hopeless? When there is no point in hoping we must be resigned and accept. When Ido was around six a doctor we saw who specialized in autism said that over the next few years it would become obvious whether Ido would be able to improve or would spend his life as a “low functioning” autistic person. This was prior to him having any communication and his true potential was totally unknown to us. She was preparing us to accept the low remedial, low expectations prognosis she saw as inevitable at that point.

I was thinking about these stories, and so many others, of professionals advising people to abandon what they saw as false hope, and then having their dire predictions turn out to be wrong. These professionals advised false deprivation of hope, in my opinion.

I have heard a few people suggest that Ido’s book may cause disappointment to parents whose children with autism may not learn to type as he does. Perhaps they believe that people with autism who have the potential to learn how to communicate their ideas are such rare exceptions that it is better if they keep silent and not give parents a chance to dream that their child too might have that capacity. Better to have low expectations, this reasoning goes, than to strive for more and have hopes dashed. Keep expectations low like this and you guarantee disappointment.

Every autistic person I know who now can express his or her ideas through typing was once thought to be receptive language impaired and low functioning intellectually. No teacher would have looked at them as children and said, “That one will be a fluent eloquent communicator.” That is because their outside appearance belied their inner capacity. Every parent of these children gambled and decided to pursue letterboard and typing without any guarantee of success.

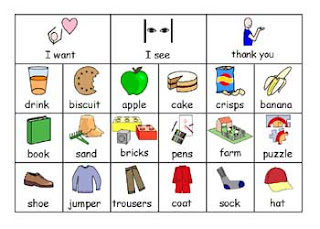

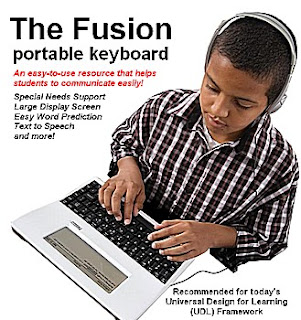

Since Ido began typing a number of children we know personally also began to get instruction in use of letterboard and typing on an iPad or other assistive technology, either by Soma Mukhopadhyay at halo.org or in another method. And every single one of them has proven themselves able to communicate. Some are more proficient than others, but none had zero capacity. (This is different than rote drills of typing and copying done in many schools. This is specialized training in typing as a form of communication).

How would it have been compassionate to these children and their parents to lower their hope to the point that they would not even try these methods? Shakespeare said. “Better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all.” In this case I would change it to, “Better to have tried and not succeeded than never to have tried at all,” because success may very well be the result.

Ido describes his experience of autism as being trapped in his own body, with a mind that understands and a body that doesn’t obey. Every nonverbal autistic communicator that we know of has expressed the same thing. How many more are waiting to find a way to express their thoughts and receive an education? Diminished expectations helps no one. I do not believe hope in this case is false, but rather, the denial of hope through misunderstanding and low expectations is what is false.